The Teen Think Tank Project kicked off its third season of Here’s the Problem podcast – focused on health equity and access to care – with John Essien, M.D., a Junior Consultant Health Economist with the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Dr. Essien and podcast host and co-founder of the Teen Think Tank Project, Kelly Nagle, have an enlightening and wide-ranging conversation about health equity, economics, and public health policy. Below is the transcript of the episode.

Introduction

Hey all, I’m your host Kelly Nagle and today I had the pleasure of talking with Dr. John Essien. John’s a health economist in the UK, but his experience spans the healthcare industry from clinical practice to field work, public work, health finance, research, and policy design. John followed his curiosity about biology and difficult personal experience into medicine. He began his career practicing in Nigeria; however, after realizing the futility of trying to overcome poverty with medicine, John pursued a degree in health economics. Today, John is working on designing and implementing strategies for sustainable health financing. In our conversation John takes us on a journey to the intersection of medicine, economics and policy and he enlightens us on how economists are a key part of addressing health equity. Enjoy!

Kelly Nagle, Host

John, thank you so much for joining me this morning on Here’s the Problem podcast. Let’s jump right in. Oh my gosh. I’m honored that you would take the time to join us.

Dr. John Essien

I’m excited to be here as well.

Kelly

Let’s jump right in. Here’s the problem – Health equity and healthcare policy, they are massive topics. You have experienced over a broad spectrum of healthcare – medicine, policy, businesses; currently, you’re a health economist, but you’re also a practicing physician. So, let’s start with your journey into medicine. Tell me a little bit about your background in both the medical and the healthcare industries.

John

Alright, so I started out my journey in medicine started out part out of, you know, the interest in human beings and, you know, just being intrigued in how, how human beings operated or works, like from a biological perspective. I would say, I remember sitting in a biology, a plant biology, class. I can still remember what it was about. It was about phloems and Cambiums, like the, the, yeah, that’s what it was about.

Kelly

I don’t think we will ever hear on this podcast again!

John

Exactly about how plants, transport, water, and minerals, like along the trunks of trees and leaves. And I, I remember sitting there thinking if this is this interesting, then how much more interesting will it be studying how, you know, the same thing’s happening with human beings. And I think that was the very first spark for me, you know, in the direction towards medicine, just the curiosity. And then this was around maybe 11, 12 years old, and then closer to the end of what we call secondary school, what you would call high school. When I was beginning to be more aware as a teenager. I grew up with my grandparents in Nigeria and just before my secondary school graduation, I lost my grandmom and I lost her to a long standing, also on her leg, which, you know, had deteriorated over time.

[She] didn’t get the proper medical attention because, you know, because of lack of knowledge and all of that, those type of influences, she went for the more traditional care, which was not successful obviously. And then by the time they eventually opted for medical care, it was already too late. And so that curiosity coupled with, you know, that loss of somebody very close, she was practically my mother because she raised me, it just drove me completely into medicine. And so I went to medical school, was successful, came out a doctor and started the best year in post medical school is usually an internship here and I was just completely knocked off, I didn’t expect that. So went to internship and it was very different from why train. Because I did my internship in the poorer parts of the country. That’s not okay.

That’s where you hear the insurgency Boko Haram. It was actually, my internship was actually in the heart of one of the, you know, biggest or I would say biggest Boko Haram, insurgents CPU. That was 2014, 2015, 2016. And so, I was exposed straight on to what poverty can do to a person’s skills. I felt like there was nothing I could do at the level of the hospital to help because, you know, thinking back to my grandmom’s story, we had so many of those types of cases where they were coming in when you literally could do nothing to help. All you could do is patch them up, cross your fingers and hope, you know, one survives. During medical school, I remember the first time we saw a case of malnutrition. At that time we were doing pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology.

That’s the women’s health. And I remember the pediatrics professor stopping the rounds because we were going on a ward round. He stopped, literally stopped the rounds, asked for somebody to go and call all the other students in the other arm of the class that we’re doing obstetrics and gynecology to come see a case of malnutrition. Because in his sense, we may never see one again. This was in the south and parts of the country; it’s a lot more, education rates is high. You know, people are much more enlightened. Malnutrition is not that much of a problem, even though you will still see it. So, to be able to have a teaching, a good teaching moment, having seen one classical case, he had to stop the rounds, ask for the other members of the class from the other side that were doing something else to come over and see this one case because they may not see it again.

And then contrast that to going up, going up north, and every patient – it started in pediatrics – every patient I saw came in with whatever they came in with classical malnutrition. Like it was, it was the add-on, it was really bad. And I remember thinking that’s really not much you can do here. I just completely kind of got a little bit disillusioned with clinical medicine because it looked like we were just there were all these tools that we could not use. And then they would come in and even with how bad they were, they couldn’t afford the treatment. And that’s when I started to think broader in terms of what my aspirations and how I could contribute. I’m thinking more policy, more structural, more finance approaches towards healthcare and yeah, going from there, I went on to work in a health in nonprofit health organization that was focused in HIV and then went into work with the health financing company.

We call them HMO’s over here, health maintenance organizations. I think you have lots of those in the U.S. as well. Our health financing system is somewhat similar to the U S and then after that I’ve still been doing a bit of clinical medicine on the side. It’s like that, you know, can’t really, really ever just leave it. And then I came over to the UK to do a master’s in health economics and since then I’ve worked in policy, have worked in more analytical health economics aspects and I’ve also worked here in the UK in a more clinical role. So yeah, that’s my story. And how, how I’ve gotten here?

Kelly

That’s quite a journey, it’s… so help me understand what health economics is and what does a health economist do it on the surface. It doesn’t seem you have health and economy. How does that work?

John

All right. So back home, I don’t know if it’s the same sentiment everywhere in the world, but back where I come from in Nigeria, when someone says he’s an economist, the first thing that comes to your mind is hmm, he’s stingy, he doesn’t want to let me research this. So, in a sense that’s right, that sense, what the economist does, but not necessarily stingy. So, a health economist basically looks at healthcare and healthcare expenditure or available resources for healthcare and says, we have so many diseases and we have so many healthcare needs as, you know, a population. And for the resources we have, if we were to dedicate all the resources we have to treating all the diseases we had, giving everybody free treatment, we would still be in a deficit. And I mean, literally every resource, because healthcare is such a condition that the more treatments you give a person, the more problems you cause.

And I don’t mean that in a sinister way. I mean that in a good way, actually. So, take for instance the, the life expectancy across the Western countries, the developed countries, it’s increased and it’s nearing the hundreds now. And what that means is you have a lot more frail people with a lot more disease conditions that you would have to treat. And a lot of them are coming in with 2, 3, 4 disease conditions. To treat these disease conditions and keep them as healthy as possible you would have to engage ever more sophisticated treatment, and these are ever more costly So the more healthy, or the longer you keep a person living, the more expenses you have to incur in continuing to keep them living. So, what the hell the court has to grapple with is coming in and saying for the resources we have, and we have very, very limited resources allocated to health, but for what we have we have to look at the best outcome that we can get for the limited resources we have.

This would mean looking at how much are we hoping to spend on a particular healthcare, say medicine and intervention, and public health project, and then saying, how much benefit do we look to achieve from this in terms of lives gained or life loss; life loss we can avert; or in terms of healthy years gained in terms of quality of life, and that’s a very big one as well. How much of that can we get for the cost that we are expending? And they have to balance that very finely with, you know, human sentiment, because there’s no price you can place in life. So, it comes down to a very fine balance between saying, oh, “I’m not going to give you XYZ million dollars, because that’s going to save only two people” to having to stare those two people in the face to say, “I’m not going to give you the money because your life is what, less than two to get.”

So, it’s a very, very delicate balance that the health economists has to thread and that, that then goes on to feed the policy of the country in terms of the healthcare policy. So a health economist basically is someone who rationalizes the available resources in hopes to get the best healthcare outcome from those resources, but on the backdrop of, you know, equity concerns, human life sentiment concerns, and, you know, wrapping all of that in a bundle that at least everybody can come to some sort of consensus with. So that was a long definition. I hope I have managed to capture it.

Watch Dr. Essien explain what a health economist does in four minutes.

Kelly

Yeah, that’s a lot of responsibility on health economists. Where do you, where is your resources put best, and I’ll put in quotes “best used” and not to dehumanize, but in a business sense, gaining the biggest return on investment. And how does that work, like with the economy? Cause there’s a financial component to this, and I would think if you were able to invest these resources in a place like Northern Nigeria or anywhere really where there’s poverty and higher disease rates, that they could better contribute to society and is that a vehicle for more profitability and a better economy?

John

Certainly, but I mean, it’s trickier with health and I think for us health practitioners, this is an aspect we don’t preach enough. The tricky thing with health is that even though research has shown, and there’s copious amounts of research, that has shown that healthcare is not only an investment in, in like that whose yields are life and, you know, quality of life improvement, but the use are also financial; the problem is to get the return, the financial return on investing in health, you would be looking at the years or you would be looking at financial returns that are not so tangible that – not that they’re not tangible – but they’re not easy to track. So, for instance, if I treated a child of diarrhea and, you know, they spent another 12 years or say 20 years before becoming the MD of a fortune 500 company, in those 20 years, there’s no economic or financial metric that’s in place to track them up to the point where they’re, that’s useful to society. So, all that information is lost, that’s the lost financial information being put on a spreadsheet.

And then by the 20th year, everybody forgets that this one child had been saved from malaria and it’s just another day in the life of the child. And on the other hand, you bring someone back from the brink of say cancer, from death from cancer and they go on to continue their normal lives and continue their normal, you know, business or whatever it is they were engaged in, and what we tend to do is view that as, “okay, they’ve gone back to work, they are productive, they’re adding monies for themselves”, but we don’t see back to say, “if we didn’t save this person, it would have been dead in three days, right?”, but now here they are five years later, still contributing positively. We just take it for granted that this person didn’t die five years ago. So, all the economic, you know, imputes that they’re putting into the society just it’s taken for granted, it’s just, yes, he’s alive.

So, this is what he should be doing. But in the real sense, the fact that they are not there, this is the reason why they are, you know, economically or financially productive. So, we don’t yet have the financial machinery or economic machinery to capture some of these more tangible financial gains that healthcare puts out. That’s why a lot of the time we think of healthcare returns and investment only in life gained or, you know, health, quality of life gained, and you know, that type of that type of thinking – we are not yet equipped to think about the things in financial – it’s just, it’s not, it’s not intrinsic, it’s not something that comes naturally. You would have to step back to think about it that way. And I think that’s kind of the problem.

Kelly

Yeah, as you’re saying this, I’m thinking the only association most people have between health and finance is just how expensive healthcare is and how it’s putting millions, particularly of Americans, in debt. Is it that we just don’t have the structure or do as you said the machinery to identify the positive financial gains that a healthy society brings, and/or is it just a mindset that needs public awareness for us to look at this differently?

John

I think it’s both. I think it’s both to a large extent, because to the second point, like I said, it’s not something that comes to us intuitively. It just doesn’t, you don’t sit down and think, oh, if I didn’t die yesterday, I wouldn’t be making XYZ amount of money. Or if I wasn’t sick yesterday, I would have, because I mean, it’s not even death, it’s economic days lost to not being at your best. In health economics, we call them absenteeism or, or even presenteeism. So, absenteeism is when you can’t be at work because you’re sick and presenteeism is when you are at work, but you’re not, you know, functioning a hundred percent because you’re ill. So, to health economists credits, they’ve been designing frameworks to kind of capture this economic value that, you know, care for health tends to bring to people.

But it’s not just the natural thing for people to think that way just yet. And maybe with more education, that will start to be a little more, you know, out there, but for now, we’re not there, we’re not there yet. And health economics as a vocation is a fairly new one, so it’s evolving as well. And they’re also at the infancy of putting out the machinery to kind of understand some of these issues. So, give it a few more years and I think it would be more out there in people’s minds, the way we view health and healthcare financing and those types of considerations.

Kelly

Amazing. So look for your name in Forbes or Time as the person who’s solving the healthcare crisis. Hopefully you’re saying it’s just a few years away. They’re going to say, I know John is on our podcast.

So, question for you – when you talk about health economics, I know you’re in the UK right now, you’re from Nigeria, so different ends of the spectrum in terms of health care, depending where you are probably in either country. When you talk about health economics, are you looking at a macro level across the globe where whatever policy suggestions you put in place could be a template for any country, or do you really have to dig down to a micro level and customize it depending on global north versus global south or in the north of a country like Nigeria versus a south of a country? Is it that granular?

John

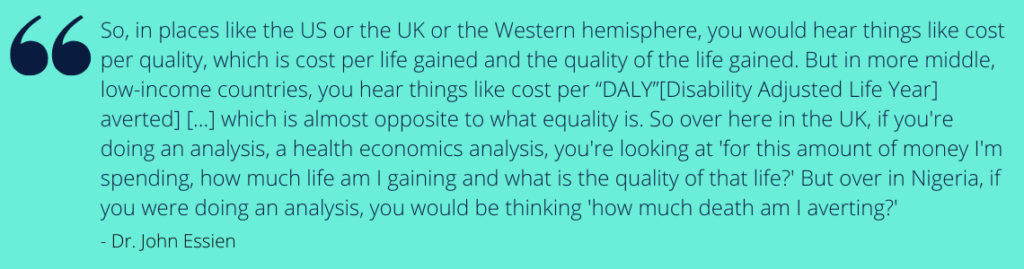

Yes. I mean, the concepts are almost universal, but much like other economic concepts. You need to plug in the context specific metrics or factorials into the particular niche you’re dealing with. And to that extent, if you’re going to, or if you want to have a successful economic analysis and make successful policies, then you have to go down to the nitty gritty, taking for instance, the health economic approaches that we use in developed countries, as compared to the health economic approaches we used in non-developed countries, you would hear things like cost per quality. So in more developed countries, they use the metric, like I said, it’s more or less a cost benefit analysis. So how much are we spending for how much gain? But now the game is in health, you know, life and quality of life.

So, in places like the us or the UK or the Western hemisphere, you would hear things like cost per quality, which is cost per life gained and the quality of the life gained. But in more middle, low-income countries, you hear things like cost per “DALY” averted. And that takes into account the differences in the epidemiology and the health expectancy of no different diseases. So, a “DALY” is a Disability Adjusted Life Year, which is almost opposite to what equality is. So over here in the UK, if you’re doing an analysis, a health economics analysis, you’re looking at for this amount of money I’m spending, how much life am I gaining and what is the quality of that life? But over in Nigeria, if you were doing an analysis, you would be thinking how much death am I averting? You see the difference now?

Kelly

Yeah, I’m actually kind of stunned. I mean, gosh, talk about equity. Wow, exactly. Or inequity in this case.

John

So that, that’s actually stunning. So when you take into consideration big killers like malaria, you know that what you’re dealing with, what’s staring you in the face, is the sheer number of children dying or people dying generally. So you’re at that point, your goal is to cut down the number of deaths as much as you can. While over here with someone with a heart attack, you’re thinking, how do I save this person and give him the best quality of life? So, the question you asked, that’s how some of the particularities of the different spaces eat into the kind of analysis we make.

Kelly

I’m literally emotional over here, just thinking about, I mean, we know there’s disparities in the world, but I don’t know it’s something about like those fancy acronyms you, you just use and putting that into context of a person’s life. Your host is speechless. I am blown away. The inequities of this world are not lost on me, but that hurt.

John

That’s what health economists have to deal with.

Kelly

Health economics make people cry.

John

Sorry. I apologize. On behalf of, health economists.

Kelly

Okay. So let’s talk about something a little more hopeful. How do you move forward? So you have these two different points of measurement – cost per quality and costs per deaths averted. How do you move forward? If you take all this good information, is there a plan for just on paper that health economists can say, “hey, this is how we can health inequities and, and provide better quality of life”, or are there other legal, political, social factors that you have to contend with to create a better policy, healthcare system, better health equity, et cetera,

John

Certainly, with health economists ingrained into the very fabric of health economics is the issue of equity and it’s really, really big in health economics. As far as, you know, doing these analysis of concern, you could do all the Excel sheet and analysis you would like to do, log all the sophisticated software, you know analysis, and at the end of the day, however good your analysis was would be an analysis and paper. And at the end of the day, you’re dealing with real human beings. So there’s no way you can escape the political, you know, and social cultural aspects of, you know, healthcare, because you have to be nested within those dimensions. And what the health economist does is try as much as they can to find a way to plug these modules into the analysis and then, even at that, it’s a piss poor job because it’s the difficult to model those kind of, you know, not very tangible things like human emotion or say cultural things that we got on a more cultural level, and all of these things are good indicators of healthcare outcome.

The data is out there to say that, to get the best healthcare outcome, religion is a very strong, you know, point. Cultural morals are a strong aspects, and it’s really difficult to model all of these into – how do you model religion for instance, or how do you model someone’s ethical, you know, dispositions? But at the end of the end of the day, what the health economist does is try as much as they can to get which parts of these that they can into their models. But then it has to still be situated within the broader socio-political context. And that is where the policy aspect comes in and where the policy makers has have to sit down and say, “this works for us, that doesn’t work for us.” We may need to look at higher costs, at lower costs in with, you know, with concentration of X or Y or Z.

And that gives it the more robust ,or at the end of the day they can have a more robust policy, healthcare policy plan for whichever population it is for. But on the other hand, or the other side of it is the equity aspect and they’re very interesting equity dilemmas. For instance, do you want to treat five kids, or do you want to treat 100 seventy year olds? Those are not very easy questions to answer. You could go one way or the other and say five kids would have accumulative of 150 years and one hundred 70 years, depending on the life expectancy of the population, it could be 20 years between the hundred 70 year olds. And so you have to balance some of those kinds of equity consents. How much healthcare are you going to deprive the richer people, you know, to, to give a wider, massive core of people healthcare? And all of that tends to need very delicate balancing and parts of what a health economist – and I mean, I was trained as a health economist and health policy analyst as well. So parts of that is, are the kind of things that you need to balance in making health care funding decisions.

Kelly

So, I’m sort of envisioning that you or any health economist needs to go on to win the presidency or be a prime minister who can then make all the policy decisions, because you would understand all this, but I don’t know of a lot of heads of state who have backgrounds in health economy. So short of that, is it feasible in the real world to have a health economist and insurance company and a government legislator all at the table putting this together?

John

I would say yes. And I, and I would say it should be the ideal thing to do. Much more developed countries and even the developing countries are currently beginning to see the usefulness of having health economists on their teams with the, with the UK, for instance, NICE [National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence] is the body that kind of helps them do some of these decision-making, difficult decision-making. So for instance, every pharmaceutical company coming into the UK has to submit the evidence for their medications. Cost-Effectiveness analysis and NICE has to be the body that does the appraisal for that. So what they do is take your evidence, look at your evidence, look back at country data and look at where the healthcare needs are; look at the cost of, you know, what your medication as a pharmaceutical company would cost the country; and then make the difficult decision of saying, “well, the UK cannot fund this or can fund this based on the health care needs that we have.”

And I think it’s a very difficult decision to make, but somebody else has got to make that decision. And for the UK NICE does that. I think for Canada, there’s a body called the Canada HTA organization. Europe has EUnetHTA, and they do that for Europe as a, as a group for America is a little bit disintegrated because America’s healthcare system is not a unified block, so that different bodies that do that for America. But, you have those set bodies start doing that for most of the much more developed countries. In Africa, we don’t have, we don’t have that yet and to be fair, health economics is still a very, very, very [inaudible] is still where health economics in the UK would be maybe 10 years old, health economists in Africa would still have been born maybe three days ago.

So it’s still in its infancy, but we are getting that to be, to be on the optimistic side. We’re getting there with, we’re seeing a lot of, you know, health economists of African descent who are actively contributing to shaping the conversation on the continent, but we have yet to see structured bodies that are, you know, responsible for the kind of things that NICE or Canada HTA would be doing for UK and Canada, respectively. But we are getting there, and I’m optimistic that in, in shorter than expected, we would have some of those policies in place.

Kelly

It’s two questions that come to mind on that. Do you find that those, that sort of regulation deters pharmaceuticals from trying to work in those countries or that those countries don’t have access to the more sophisticated type of treatments because pharma doesn’t want to go through that regulatory system or doesn’t want to be, and I’m assuming so, correct me if I’m wrong, doesn’t want to be capped or told how they can or cannot run their business?

John

No, quite on the contrary, they cannot afford to do that. So, for instance the difference in the US, and part of the reason, or at least in my sense, part of the reason why health care is really expensive in the U S is the absence of these kinds of, you know, regulatory bodies. The FDA, for instance, just regulate; it does some of what NICE does for the UK, which is things like scoping for new health or new drugs or health technologies and, you know, guiding them through the approval processes, but it stops there at the approval. NICE takes if the step further to say, “even though your drug is approved, do we need it for our population, is it something that’s cost-effective for our population and can we afford it?” So, and these pharmaceutical companies cannot operate solely in America.

Obviously, they, they, they make the big bucks in America, but they can’t survive only in America so they have to make inroads into other parts of the world. And if they have to they must go through these gatekeepers. And so, Australia, Canada, which has, and, and you would notice that most of the countries that have these kinds of gatekeepers or countries that have universal health, you know, for the whole population, the UK has free healthcare for everybody. Canada has some sort of, you know, part payment, but it’s mostly free. Australia is this a similar story and most of most of Europe has some structured universal healthcare system going on. And so with that, it’s easier for the countries to negotiate against the pharmaceutical companies. So for you to be able to bring in any medication into the country, you have to go through those bodies. And if you don’t, then there’s really nothing they can do for you.

Kelly

So, you lose the market.

John

Yeah, you lose the market that way. They’re able to negotiate better and they’re able to, you know, kind of set limits and what comes into the country, what person, what is beneficial to the country in terms of financing and what isn’t. And so, there’s a kind of differences between, you know, most of the other developed countries and America. In America, as long as FDA has approved it for that particular use, if somebody is willing to buy the drug at whatever price they want to buy it, it’s an open markets. Yeah.

Kelly

Yeah. So, my second question, when you were talking about that, which makes me think about this even more from what you just said, could an answer be that more countries develop these regulatory bodies, where it’s like, all right, well, XYZ pharmaceutical can’t get into the market because they don’t want to cap their profits, we’ll just go to next country that has an open market, but is it sort of peer pressure if all of Europe has regulatory body, Asia, Africa, then it’s sort of like, you know, safety and numbers? Where pharmaceuticals have to then bow to that expectation that you cannot jack up your prices and put people in debt to give them healthcare. Is that reasonable?

John

Yeah, it’s, it’s, it’s an interesting…it’s an interesting question from the perspective of pharmaceutical companies. And this is not, this is not to attempt to throw a shade at pharmaceutical companies because they do an incredible job of keeping us alive. If the argument for, from pharmaceutical companies is anything to go by, it goes this way – that America pays for the whole world’s healthcare, in some sense, because by being, you know, the, the most open markets, it allows pharmaceutical companies the leg room to do all the, to spend all the money they need to spend in R and D and innovation and all of that. And then off the back of that, countries, like the UK, Canada of do can do their, you know, one front negotiation. And then one would argue if America was to go the way of all the other countries with the one block type of negotiating, pharma prices for the country, how much hurt would that do to pharmaceutical companies? And I’m not very privy to the financials of pharmacies to go companies so I can’t, you know, make the moral argument of, oh, they’re not making as much money as they claim, or they are making more money than the claim, so it’s, it’s a tricky conversation to have. Going by the argument that America pays for the healthcare needs of these other countries whose markets are not so free, but on the other hand, I think it, it, there’s, there’s another point that is kind of leading in that conversation.

And that’s the point of over treatment. Part of the work of a health economist is not just to is not just to find the most cost-effective treatment. It’s also to help, you know, whoever’s funding or even the citizens avoid over-treatment, because of a treatment on its own is the problem not just financially, but also health wise, and people are going to get over-treated if the treatment is free. And the UK sees a lot of that as well. So, part of that gatekeeping is in wholesaling, how much treatments people get, because if it’s free, then they’re going to get it. They’re going to get a CT for just popping their head on the wall and having a little bruise when that’s not necessary. And so those are some of the, the, the dichotomies between, you know, free markets where you have to pay, and you have to carry at the back of your mind that this is going to cost me.

And so you’re not accessing that healthcare as ravishly as you would have in a country where it was free. And then in the free country where the country itself has to do the gatekeeping, but on the part of the citizens, it’s a free for all, you know, buffet, healthcare. So it’s not, it’s not very, it’s not very straightforward. It’s a delicate argument to have, but I guess it’s, we’re going to see how we unfold. We’ll see how it unfolds with the policy progress that is unfolding across the world generally, but at least that’s what it is now.

Kelly

Awesome! So what’s some of the work you’re doing now in terms of research and building models? I know you’re working with the UN, I’m sure you’re doing a million other things as well, but what are some of the things you’re working on to address this, to, to come to some sort of conclusion, how do we dispense healthcare equitably and, and at least in America’s case in some sort of affordable way?

John

Right. Okay. I mean, America’s case is really interesting. Unfortunately, I’ve not done much work in, in the American continent or subcontinent. Much of the work I’ve done is for an in Africa and

Kelly

Alright, keep America out of it. We’re complex..

John

Yeah. I mean, I think I could, I mean, I could talk about America for the whole day because America’s always on the news and healthcare is a very, very big topic in America. So, I mean, we could have that conversation for well the whole day, but –

Kelly

Part two of the episode –

John

In terms of work that I have, like actually done health economics work I have done, it’s been in Africa so recently and I mean, before, before I jumped on the call, I was actually typing out a, some sort of policy analysis of the data that we have gathered so far. And so, we’re working on the cost of action and cost of inaction of funding some disease areas in, in Africa. So, the idea was most of the funding going to Africa has been going to three major diseases: HIV, TB, and malaria. But just below that, in terms of the number of deaths incurred from those diseases are childhood diseases like diarrheal disease and lower respiratory tract infection. And so will, what we’ve been doing is saying so you can either neglect these, these pieces, or you can fund their treatment, or even if not treatment programs to prevent, prevention programs, whichever it is.

So, and both of them are going to cost you, basically. What we’re saying is: which costs would you rather have? Would you rather bear the cost of not funding them and then we built a model to show you what it would cost you to not fund them? Or would you rather fund them and then we also show you what it will cost to, you know, to fund on, you know, the strategies to curb these diseases. And then the data speaks for itself. So what we’re doing is building the costing models and letting the data speak. So you can see from a macroeconomic level and from a microeconomic level, the cost of not anything. And you can see from the same perspective, the cost of doing something. And thankfully from my days the cost of doing something is much less than the cost of doing nothing. And so both, both in terms of, you know, in financial terms and in life and quality of life terms. So that’s, that’s something that’s been exciting to see. And that’s, that’s what I’ve been working on in the last few months.

Kelly

Are you finding that policymakers and governments are receptive to that data and moved by it?

John

Luckily this project is funded by the UN and it is for rapid implementation across seven countries in Africa. So, I said luckily, because it’s not always that way. And that’s not just, you know, in African countries, it’s, it’s a global problem where the, the situation between and between policy analysis or economic analysis, policy analysis, policy recommendations, and then the actual, you know, execution of that policy is, is a very long situation – there’s a long time gap between that. And the problem with that is that by the time countries then decide to enact the policies that way, you know, that that was come up with three, four years ago, the landscape has changed and you’ve not factored in, into your new execution, the changed landscape and your execution becomes problematic. And it looks like the policy was not, you know, reasonable, but it’s just that the time gap between policy recommendation and execution, you know, a lot has happened in that time. And that’s, that’s been a big concern for health economists, or health policymakers. And it’s something that people in the health space are looking to work on and try to see how that can be shifted, but it’s a consent worldwide.

Kelly

Has there had to be, and this might be a stupid question, at least on the health economists’ side, has there had to be a major shift because of the pandemic? Or has that sort of, kind of just gone by and not necessarily affected the work you’re doing at least with this UN project?

John

Generally, there’s been a big shift. I don’t think there’s anything that the pandemic has not affected. It’s just, it’s been a huge, huge, huge, huge shift. So, with the project, and I don’t know, to, to the extent that we are erroneous that in that regard, but with the project, we had to make the conscious decision to turn a blind eye to the pandemic and act like the pandemic did not exist. Because if we were to, you know, factor in the pandemic, then the, it would have done a lot to the model. So, we decided to look at lower respiratory tract infections that did not include, you know, COVID-19, which is also a lower respiratory tract infection. To be fair, it would, it would probably have worked in our favor or in the favor of, you know, what we were hoping would be the case, but then it wouldn’t be the kind of data that would be, wouldn’t be a – how do I put this? It would be a skewed data in that sense, and we –

Kelly

Yea, it would be circumstantial, right?

John

Exactly. We didn’t want anything circumstantial to skew the data that we were trying to present. We wanted to get as close to the actual reality as possible. And even though a one-off would have been in the favor of what we were trying, trying to see, or what we were hoping would be the case we go in there – I mean, you go in, you go into data analysis with the hope, sometimes it’s not what you hoped for, and you adjust your knowledge and understanding about what the landscape is. Sometimes it’s what you were hoping for and, you know, the data bears itself out, but you don’t want to taint whatever you’re doing with, you know, these kind of one-offs that then give a very, very skewed picture. And so that’s why we did not include COVID-19, but then the extent to which that was wrong or right we can’t really tell. This was just the logic we were going with. And so, yeah, that’s that we had to, we had to just show COVID-19 as an aside, just so you know. Yeah.

Kelly

Well, we talk a lot about data integrity at the Teen Think Tank Project, and following the data and not creating sort of perceived notion and then interpreting data and questioning those interpretations, you know, is the, the quick blurb I’m getting on the news, you know, about this data or stats, you know, really telling the whole picture, or we just kind of taken out of context for something that we’re going to apply to this cause it sounds good? So I love your comments about, you know, hoping for an outcome, but following the data and data and building your case. Yeah,

John

Exactly, exactly. For instance, my dissertation project was trying to look at pandemics and how effective testing, like widespread testing would be doing a health economic analysis of effective, widespread spread testing could be for pandemics. And the data wasn’t good. I was hoping that, you know, widespread testing would be something that would be, you know, very, very helpful for pandemics and health outcomes, but it wasn’t good. And to report that…

Kelly

Did you do that thesis? Did you do that dissertation before COVID-19?

John

I did it, and so my, yeah, my master’s education was in the very heart of COVID-19 and by then we didn’t have vaccines. So what we had a way to test for it, and that was the only kind of public health measure that countries were putting in place to curb it to the extent that they could. And, I was hoping, you know, testing would be a good measure, it just wasn’t that good a measure from a health economics perspective. But then, and this goes back to what we were saying, from a much wider social political context it then becomes a good public health measure if you see what I mean. So from a much wider socioeconomic group to keep, you know, keep the societal piece to kind of rein people in to reduce the burden on, on the hospitals, then it becomes a good measure. But taking it in isolation, it’s not o, you know, it’s not so robust because it doesn’t really do much for the apart, from social distancing and staying home. It doesn’t really do much for health outcomes going forward for the person that you understand. So those are some of the considerations that, but at the end of the day, we just followed the data and make recommendations based on the data.

Kelly

Which is good to know because you’re looking at it specifically from an individual health outcome versus a public health emergency stemming, you know, putting these other measures into place to stem the disease, support the hospital system… Interesting. We’re going to turn over every rock and look at it every different way to kind of get the whole, the whole picture, because as you were saying, I was like, “oh my gosh, I can just see the news now: like somebody, somebody in American politics is gonna hear our podcast. That’d be a great problem to have here. Hear our podcast and this doctor says we don’t need widespread testing the entire. Time out! Let’s put this into context.

John

You have to put it into context. They have to put all of it into context. In the wider context, it becomes, you know, a good public health, but in, in narrow context of just testing as one, you know, single.. it’s just like saying, if you put it in, in a regression model, for instance it would be effective, but then it would be compounded by all that, all the factors in the model. And then if it took it out of the regression model and try to, you know, if you correct that for the other confounders, you would find that, that the, you know, the effect wasn’t that big. But put in with all the health economy or the public health measures, then it makes it be a big difference. That’s kind of the sense where, you know, what the data said. That’s, that’s what, that’s what data is. You have to pull it right.

Kelly

Yep. Very important. It’s the foundation of so many decisions, data-driven decisions. I loved our whole conversation. So many important aspects of health equity and healthcare. You’ve made me laugh. You’ve made me cry. We’re ending, we’re ending, alas. John, it’s been such a pleasure. So enlightening to understand the intersection of healthcare and economics more and something that can be a vehicle for helping to understand that and put into context cost analysis and how we approach that and maybe take another step forward to achieving health equity in this world.

John

I’m always saying, I’m always excited to talk about healthcare and health economic and clinical medicine. It was, it was a very good conversation. Kelly, thank you very much for having me.

Here’s the Problem podcast is a production of the Teen Think Tank Project and engages both our students and our listeners in thought-provoking conversations. Each episode thought leaders and experts join podcast host and Teen Think Tank Project co-founder, Kelly Nagle, to explore a specific problem facing our society. We rely on fact-based information, listen to understand, and challenge our own ingrained perspectives. Because at Here’s the Problem Podcast we believe that this is the only way to chart a course towards cooperation, empathy, and ultimately effective change.

Here’s the Problem podcast is available on the Teen Think Tank Project website, iTunes, Spotify, and Google Play.