The inadequacies of federal healthcare coverage

The United States Medicaid & Medicare programs, first established in 1965, aim to provide medical insurance to low-income populations (Medicaid, n.d.). It is one of America’s largest entitlement programs. But despite the mission of providing comprehensive health coverage to low-income people, we continue to see the quantity of non-ederly populations without health insurance increasing. If this is the case, it is reasonable to ask whether or not Medicaid is successfully fulfilling its intended goals.

Medicaid A, B, C, D

Medicaid is a government program, administered at both the federal and state levels, that intends to help lessen the burden for low income individuals in America in need of access to the healthcare industry. Medicaid is split into 4 parts: A, B, C, and D.

Part A covers inpatient/hospital coverage as well as skilled nursing visits. Under part A, patients may pay a monthly premium and/or a recurring coinsurance, an amount paid by a patient in a timely manner formally determined by the receiving party.

Medicaid part B covers outpatient/medical coverage. Under part B patients must pay a monthly premium to receive the benefits of annual healthcare checkups. Regular visits to family physicians as well as some specialty offices are covered under part B.

Medicaid part C is a dual program that includes both parts A and B. It is offered by private companies and is, therefore, more selective.

Medicaid part D provides coverage for prescription drug costs through private plans. Beneficiaries who qualify for Medicaid or an MSP in a state, automatically qualify for Extra Help (also known as the Low-Income Subsidy program) to help pay for the costs — monthly premiums, annual deductibles, and prescription copayments — related to Medicaid Part D (Medicaid n.d.).

Title XIX

Title XIX of the Social Security Act Amendments, signed by Lyndon B Johnson in 1965, which initiated the Medicaid and Medicare programs, listed the guidelines for both. Medicaid continues the tradition of past welfare programs in that much of its implementation is solely based on state requirements. Under Public Law 89-97, the governor of each state determines an agency put in charge of forming a sound structural plan for administering Medicaid. This plan is binding and determines the groups of individuals to be covered, health care services to be provided, methods for paying providers, provider qualifications, and the administrative activities necessary for everything to reach fruition. The plans developed by the states are referred to as SPAs (State Plan Amendments) and are sent to the CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) to be reviewed and further edited. Once complete, any further editing will have to be done through a lengthy process of back and forth contact between the state agency and the CMS (Bane 2021).

Statutory Eligibility

Under Medicaid, the children, the blind, those who are physically disabled, specific mentally disabled patients, and others receive automatic coverage, regardless of the SPAs administrative guidelines. Aside from the automatically qualifying populations mentioned above, the vast majority of those enrolled under Medicaid lack an alternate form of health care insurance and have to resort to applying for Medicaid. To be eligible, persons must earn an amount either under the state poverty lines (stated in the SPA) or under a specific rate that can vary based on family size, occupation, past medical history, and more (HHS n.d.).

The graph below displays the fiscal revenue per year of those categorized under the poverty line.

Individuals earning this amount are the ones most likely to receive Medicaid, others may have to pay larger portions out of pocket (Loper 2022).

In perspective, a singular individual’s annual groceries costs roughly $2,641 and annual living expenses are roughly $38,266 per year (Bundrick 2021). As displayed, those grouped above the poverty line do not make enough money to live even mediocre lives.

Residential Eligibility

Only U.S. citizens or “qualified aliens” are eligible for Medicaid (Summary of Immigrant Eligibility Restrictions Under Current Law, n.d.). Considering that nearly 15% of America’s population is composed of immigrants on either visas or green cards, it is apparent that Medicaid does not reach the entire population (Population Division | Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.). Those who have not lived in America for some time and/or are in the lengthy process of receiving American citizenship can not receive the benefits of Medicaid. Immigrants who are working in physically and/or mentally exhausting conditions are left with no option but to acquire hefty debts from healthcare.

These immigrants fit most of the requirements for receiving Medicaid, and the majority of them pay their fair share in taxes as well. In a study conducted by American Voices, it was discovered that “between 50 percent and 75 percent of unauthorized immigrants pay federal, state, and local taxes.” Those who follow tax guidelines on the meager salary they earn should receive the proper benefits they deserve (Feinleib & Warner, 2007). Yet these individuals are being denied affordable healthcare coverage.

Federal Government Expense

Medicaid expenses have been steadily increasing since the program’s inception. Medicaid’s rate of growth has trampled that of the American GDP and displays a clear increase in the rate of uninsured individuals.

Since 1980, Medicaid has increased from 2.8% of the government’s expenses to greater than 10% in 2014 (Broaddus 2012). Currently, the government spends nearly $650 billion on Medicaid (and Medicare) (Medicaid Enrollment & Spending Growth: FY 2021 & 2022, 2021). At this exponential rate, Medicaid will be upwards of 20% of the federal government’s expenditure by 2050.

Immense expenses such as these will only force the government to make difficult funding decisions in the future.

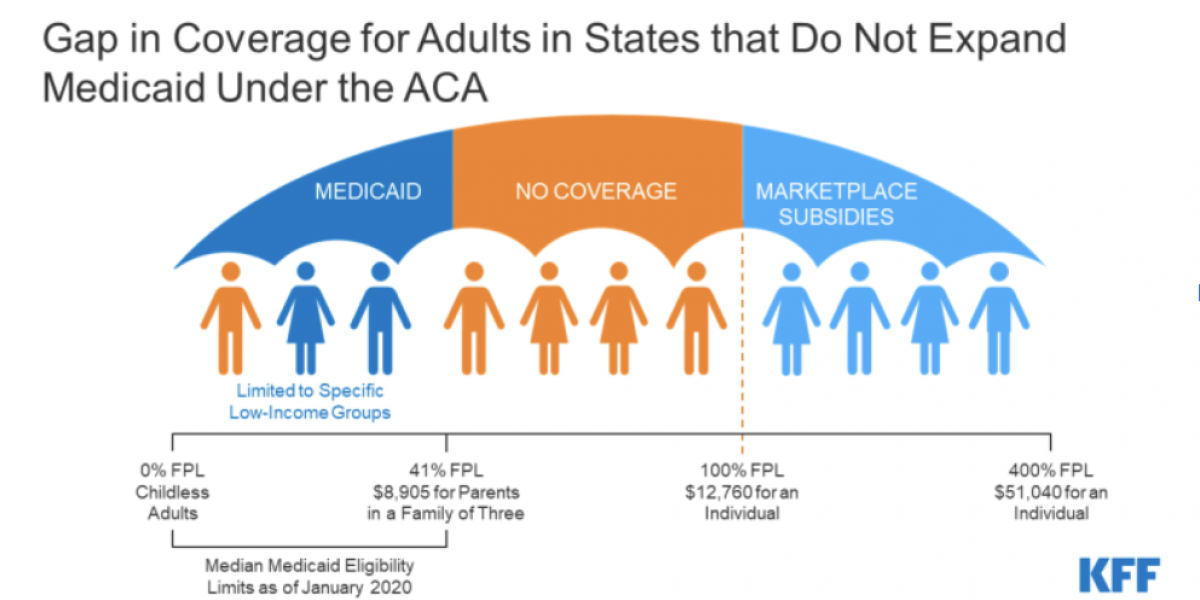

The Coverage Gap

Despite the growing expenses associated with the administration of state-run healthcare, gaps in Medicaid eligibility have caused impoverished uninsured adults to amount massive healthcare debts. In recent months, millions have gained health insurance coverage through Medicaid as a result of the economic effects of the pandemic as well as the maintenance of eligibility and continuous coverage requirements tied to accessing the benefits of Medicaid. The increasing amount of adults eligible for Medicaid insurance has caused the poverty line to become lower. Simply put, the higher demand for Medicaid has caused it once again to become steeper and harder to receive.

What's Next?

At a time when many are losing income and potentially health coverage during a crisis, these eligibility gaps leave many without an affordable coverage option and only contribute to growth in the uninsured rate. Unfortunately, there is no surefire way to decrease the rise in uninsured individuals. Experts hope that with the decline of the pandemic individuals who lost jobs may rejoin the occupational field and regain their privatized insurance provider.

Works Cited

Bane, F. (2021, December 1). History. CMS. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/History

Broaddus, M. (2012, March 28). Federal Government Will Pick Up Nearly All Costs of Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-government-will-pick-up-nearly-all-costs-of-health-reforms-medicaid-expansion

Bundrick, H. (2021, April 29). Average Monthly Expenses: From Single Person to Family of 5. NerdWallet. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/finance/monthly-expenses-single-person-family

Feinleib, J., & Warner, D. (2007, December). The Impact of Unauthorized Immigrants on the Budgets of State and Local Governments. Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/reports/12-6-immigration.pdf